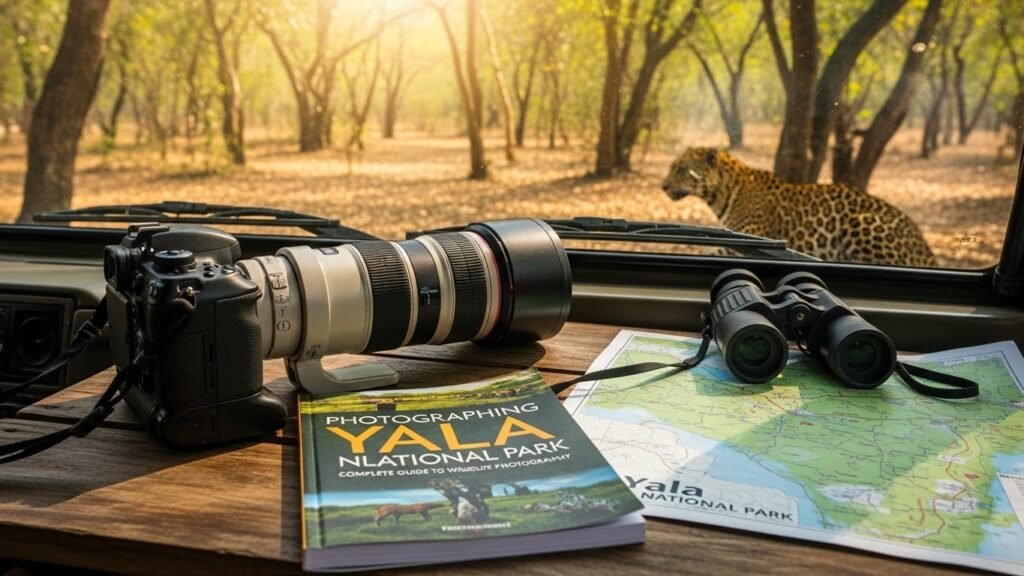

Yala National Park presents both exceptional opportunities and unique challenges for wildlife photographers. The combination of high leopard density, open terrain, and habituated wildlife creates scenarios that photographers dream about. However, the harsh light, dust, vehicle vibrations, and unpredictable animal behavior demand technical knowledge and adaptability. This guide covers everything from essential gear to advanced techniques for capturing Yala’s wildlife at its best.

Essential Camera Gear

Camera Bodies

A camera with fast autofocus, good high-ISO performance, and decent burst rate is essential for wildlife photography. Modern mirrorless cameras excel in Yala’s conditions, offering silent shooting modes that don’t disturb animals, excellent autofocus tracking, and in-body stabilization that helps when shooting from moving vehicles.

What you need: Ideally, bring two camera bodies—one for telephoto work and another with a shorter lens for landscapes and closer encounters. This eliminates lens-changing in dusty conditions and ensures you never miss a shot because you have the wrong lens mounted. If budget or weight limits you to one body, prioritize a camera with weather sealing and strong autofocus performance.

Settings optimization: Set your camera to back-button focus (separating focus from the shutter button), which gives you better control over focus tracking. Use continuous autofocus mode with subject tracking for moving animals. Enable your camera’s fastest burst mode for action sequences. Most importantly, shoot in RAW format—Yala’s challenging light conditions mean you’ll need maximum flexibility in post-processing.

Lenses: The Most Critical Decision

Lens selection makes or breaks wildlife photography in Yala. The open terrain means animals are often distant, requiring serious reach.

The ideal setup: A 400mm f/5.6 or 500mm f/5.6 lens for wildlife, paired with a 24-70mm or 24-105mm for landscapes and context shots. Full-frame users get the focal lengths as marked; crop-sensor users benefit from the 1.5x or 1.6x multiplier, making a 300mm effectively 450-480mm.

Budget alternatives: If 400mm+ lenses are beyond budget, a 70-300mm or 100-400mm zoom provides versatility. You won’t get frame-filling leopard shots from distance, but these lenses still capture excellent images of closer wildlife and offer flexibility for various situations. Teleconverters (1.4x or 2x) extend reach but reduce light-gathering ability and autofocus speed—use them judiciously.

Wide-angle importance: Don’t neglect wide-angle capability. Some of Yala’s most compelling images show animals in their landscape context—a leopard on a rock with scrubland stretching to the horizon, or an elephant herd at a lagoon against dramatic skies. A 16-35mm or 24mm prime captures these environmental portraits beautifully.

What NOT to bring: Heavy, extreme telephoto lenses (600mm+) become burdensome in Yala’s heat and vehicle constraints. Unless you’re a professional wildlife photographer with support systems, stick with more manageable focal lengths. Similarly, avoid bringing too many lenses—dust is the enemy, and every lens change risks getting particles on your sensor.

Essential Accessories

Bean bags: These are absolutely critical and arguably more important than a tripod. A good bean bag (or two—one large, one small) stabilizes telephoto lenses on the jeep’s frame or door, dramatically improving sharpness. You can bring empty bags and fill them with rice or lentils at your accommodation, then empty them before departure to save luggage space and weight.

Lens cloths and cleaning supplies: Dust infiltrates everything in Yala. Bring multiple microfiber cloths, a lens cleaning solution, a rocket blower for removing dust without touching lens surfaces, and lens pens. Clean your gear each evening—accumulated dust degrades image quality and can damage equipment.

Extra batteries and memory cards: Bring at least three batteries per camera body. High burst rates, live view usage, and LCD screen reviews drain batteries faster than you expect. Memory cards should be high-speed (minimum 150MB/s write speed) and ample capacity—budget 64-128GB per day of shooting. Always format cards in-camera before each safari.

Protective gear: A rain cover for your camera protects against unexpected downpours during green season. Even in dry season, a simple plastic bag or shower cap can protect gear from dust when driving between locations. A UV or clear protective filter on each lens safeguards expensive front elements from scratches, dust, and impacts.

Support and comfort: A padded camera strap or harness distributes weight during long days. Consider a photographer’s vest with multiple pockets for quick access to memory cards, batteries, and cleaning supplies without digging through bags.

Understanding Yala’s Light

Light makes or breaks wildlife photographs, and Yala’s tropical location creates both opportunities and challenges.

The Golden Hours

The first and last hours of daylight provide the most beautiful, flattering light for wildlife photography. Dawn light (6:00-7:30 AM) is soft, warm, and directional, creating modeling on animal features and bringing landscapes alive with color. Similarly, late afternoon light (4:30-6:00 PM) paints subjects in golden tones and creates long shadows that add drama and depth.

Why it matters: Side-lighting during golden hours reveals texture in fur and feathers, creates catchlights in animals’ eyes that bring portraits to life, and produces images with three-dimensional quality lacking in harsh midday light. Schedule your safaris to maximize these prime hours.

Technical approach: During golden hours, you can often shoot at lower ISOs (400-800) while maintaining fast shutter speeds. The directional light allows for proper exposure of both subject and background, reducing the need for significant post-processing adjustments.

The Midday Challenge

Between 10:00 AM and 3:00 PM, Yala’s sun becomes harsh, creating high contrast, deep shadows under animals’ features, and washed-out highlights. Most photographers consider this period “bad light,” but it’s also when the park is less crowded, and animals congregate at waterholes.

Making it work: Shoot slightly underexposed to preserve highlight detail in bright areas, knowing you can lift shadows in post-processing. Focus on behavioral shots rather than portraits—action and interaction matter more than perfect lighting. Silhouettes can be powerful when the sun is behind your subject. Embrace black-and-white processing for midday images, where harsh contrast becomes an asset rather than a problem.

Water opportunities: Animals drinking or bathing create natural reflections that add visual interest and fill in harsh shadows with reflected light. Position yourself with the sun behind you when possible at waterholes, or embrace creative backlit situations.

Overcast and Stormy Conditions

Green season often brings cloud cover and dramatic storm conditions. Many photographers avoid these periods, but overcast skies act as giant diffusers, creating soft, even light perfect for capturing animal portraits and behavior without harsh shadows.

Advantages: Even lighting reduces contrast, making exposure simpler. Colors appear more saturated than under harsh sun. Dramatic cloud formations add atmosphere to environmental portraits. Animals often become more active before and after rain.

Technical adjustments: You’ll need higher ISOs (1600-3200 or more) to maintain fast shutter speeds in reduced light. This is where modern cameras’ high-ISO performance proves valuable. Watch your shutter speed carefully—even with stabilization, you need 1/500 second minimum for wildlife, faster for action.

Camera Settings for Different Scenarios

Leopards: The Prize Subject

Leopard photography demands technical excellence—these are the shots you came for, and you might get only seconds to capture them.

Standard approach: Aperture priority mode at f/5.6-f/8 (depending on your lens), ISO 800-1600 (adjust based on light), continuous high burst mode, and autofocus set to continuous with subject tracking. This combination prioritizes fast shutter speeds (ideally 1/1000 second or faster) while maintaining reasonable depth of field.

Why these settings: F/5.6-f/8 provides enough depth to keep the leopard’s face sharp even if it’s slightly angled while blurring distracting backgrounds. Higher ISOs ensure shutter speeds fast enough to freeze motion—leopards move quickly, and vehicle vibration adds blur. Continuous autofocus tracks the cat if it moves, and burst mode captures sequences as behavior unfolds.

Behavioral sequences: When a leopard is active—stalking, marking territory, or interacting with cubs—shoot in bursts but be selective. You don’t need 500 nearly identical images, but you do want to capture the peak of action or the decisive moment in an interaction.

Resting leopards: For a leopard lounging on rocks, you can reduce ISO for cleaner images, use single-shot autofocus, and take time to compose carefully. These situations allow for artistic choices—tighter portraits emphasizing facial features and eye detail, or wider environmental shots showing the cat in context.

Elephants: Size and Drama

Elephants present different challenges than leopards—they’re larger, often closer, and create opportunities for both portraits and behavioral photography.

Standard settings: Aperture priority at f/7.1-f/9 (you can afford slightly smaller apertures with larger, less mobile subjects), ISO 400-800 in good light, continuous autofocus. Shutter speeds of 1/500-1/1000 second handle most situations unless elephants are running or engaging in vigorous activity.

Group shots: When photographing elephant families, consider depth of field carefully. F/8 or smaller keeps multiple animals at slightly different distances reasonably sharp. Focus on the nearest elephant’s eye and let depth of field do the rest.

Detail shots: Don’t just shoot whole elephants. Trunks, eyes, tusks, textured skin, and interactions between family members create compelling images. For these details, open up to f/4-f/5.6 to isolate subjects from backgrounds.

Action sequences: Elephants bathing, dust-bathing, or sparring create dynamic photo opportunities. Increase shutter speed to 1/1250 second or faster to freeze water droplets or airborne dust. Anticipate the action—watch for telltale signs like trunk filling with water before the spray or positioning before a dust throw.

Birds: Speed and Precision

Yala’s avian diversity offers endless photographic opportunities, but birds demand the fastest shutter speeds and most precise autofocus.

Flying birds: This is the ultimate technical challenge. Use shutter priority at 1/2000 second minimum (1/3200 for fast-flying species), wide-open aperture (f/4-f/5.6), and let ISO rise as needed (easily 1600-3200). Continuous autofocus with tracking is essential. Practice panning smoothly, starting before the bird enters frame and following through after release.

Perched birds: Easier technically but requiring patience and careful approach. Aperture priority at f/5.6-f/8, ISO 400-1000, shutter speeds 1/500 second or faster. Focus precisely on the eye—a sharp eye is non-negotiable in bird photography. Watch for behavioral cues—birds often open their wings or vocalize before flying, giving you seconds to prepare.

Water birds: Species like painted storks, spoonbills, and herons feeding in shallow lagoons provide excellent opportunities. They’re often tolerant of vehicles and engage in photogenic behaviors. Position yourself with sun behind or to the side, watch for reflections, and be patient—the best shots come to those who wait for compelling action rather than just recording presence.

Composition Techniques for Yala

Rule of Thirds and Beyond

The rule of thirds—placing subjects along imaginary lines dividing the frame into thirds—creates more dynamic compositions than centering subjects. Position leopards, elephants, and other primary subjects at intersection points, not dead center.

When to break it: Tight portraits and symmetrical subjects (an elephant walking directly toward you, a leopard staring directly at the camera) often work better centered. Trust your eye and the specific situation.

Eye-level perspective: Whenever safely possible, shoot from the animal’s eye level rather than looking down. This creates more engaging, intimate images. In a safari jeep, this is challenging—sometimes you’ll need to shoot through windows or position yourself low in the vehicle.

Negative Space and Environmental Context

Yala’s open landscapes invite environmental portraits—showing animals small in the frame with expansive sky, scrubland, or water surrounding them. This approach conveys the sense of place and habitat that tight wildlife portraits lack.

Technical approach: Use wider focal lengths (24-200mm range), smaller apertures (f/8-f/11) to keep both animal and landscape sharp, and compose with the animal placed strategically within the broader scene. Look for leading lines—roads, shorelines, tree lines—that draw the eye toward your subject.

Foreground Elements

Using vegetation, rocks, or branches in the foreground adds depth and three-dimensionality to images. Shoot through partial obstructions (with subject still clearly visible) to create layers in your composition.

How to execute: Use wider apertures (f/4-f/5.6) to throw foreground elements out of focus while keeping your subject sharp. This technique works beautifully with leopards in dappled shade or elephants feeding in brush.

Behavioral Moments Over Portraits

While beautiful portraits have their place, images showing behavior, interaction, and action tell richer stories. A leopard mid-yawn, elephants greeting with intertwined trunks, a deer fleeing from danger—these moments convey the dynamism of wild lives.

Being ready: You can’t predict many behavioral moments, but you can position yourself for probability. Watch animal body language for cues. An elephant with trunk curled and ears back might charge. A leopard shifting weight and focusing intently might pounce. Having your camera ready and settings dialed in means you’ll capture these fleeting moments.

Working from a Safari Vehicle

Stability Challenges

Safari vehicles bounce, rock, and vibrate, introducing motion blur into your images. Proper support and technique minimize this problem.

Bean bag technique: Place your bean bag on the vehicle’s frame, door edge, or window ledge. Nestle your lens into the bag, applying gentle downward pressure. This creates a stable platform that absorbs most vibration. Don’t grip the lens tightly—tension transmits vibration. Rest it naturally in the bag and use a light touch.

Body positioning: Brace yourself against the vehicle structure. Tuck your elbows against your body. Breathe steadily and press the shutter during the natural pause after exhaling. If the vehicle is moving, wait for it to stop before shooting—ask your driver to pause when you have a shot opportunity.

Shutter speed compensation: Add 1-2 stops faster shutter speed than you’d use on solid ground. If you’d normally shoot at 1/500 from a tripod, use 1/1000 from a vehicle.

Positioning in the Vehicle

The best shooting positions are standing or kneeling in the back of an open jeep (where allowed and safe), or shooting through open windows. These positions minimize obstructions and give you freedom to adjust angles.

Window shooting: When shooting through windows, get your lens as close to the opening as possible without touching the frame (which would transmit vibration). If you must shoot through glass, press the lens hood directly against the window to minimize reflections and maximize clarity.

Roof hatches: Some vehicles have roof hatches allowing you to stand and shoot. This elevated perspective is excellent for larger animals but creates a looking-down angle that’s less flattering for smaller subjects.

Vehicle Etiquette for Photographers

Communicate clearly with your driver about what you want—specific positioning, stopping smoothly, approaching slowly. Good drivers understand photography needs, but you need to articulate them.

Don’t: Ask drivers to break rules (driving off-road, approaching too close) or monopolize a sighting when other vehicles are waiting. Do share sightings with nearby vehicles—karma in safari photography is real, and courtesy often comes back to you.

The Digital Workflow

In-Field Management

Review images on your camera’s LCD regularly, but don’t obsess over every shot—you’ll miss moments while chimping. Glance at histogram and highlights to ensure proper exposure, especially in harsh light. Delete obviously failed shots (missed focus, closed eyes, excessive blur) to free memory and simplify later culling.

Backup: If possible, back up images daily to a laptop, external drive, or cloud storage. Memory card failures are rare but devastating. Don’t risk losing your once-in-a-lifetime leopard shots.

Post-Processing Approach

Modern RAW processors (Lightroom, Capture One, DxO) can recover remarkable amounts of detail from shadows and highlights, but starting with properly exposed images makes processing easier and yields better results.

Basic workflow: Import RAW files, cull ruthlessly (keep only your best), make global adjustments (exposure, contrast, white balance), perform local adjustments (dodging and burning, selective sharpening, gradient filters), apply noise reduction if needed at high ISOs, and sharpen appropriately for output.

Yala-specific adjustments: The dusty atmosphere often creates haze that reduces contrast and color saturation. Use dehaze tools judiciously—they’re powerful but can create unnatural-looking images if overused. The warm light of golden hours can create overly orange tones; adjust white balance toward neutral while maintaining the warm feeling. Harsh midday light often requires shadow recovery and highlight reduction to balance contrast.

Creative Processing

Don’t hesitate to try black-and-white conversions, particularly for images with challenging light or distracting color casts. Yala’s graphic landscapes, strong shapes, and dramatic skies often work beautifully in monochrome. Dust, heat shimmer, and high contrast that fight against color images can become assets in well-processed black-and-white.

Ethics and Best Practices

Respect Trumps Photography

Never prioritize getting a shot over animal welfare. If your presence is clearly causing stress—animals moving away, showing defensive behaviors, or abandoning activities—back off. No photograph is worth disturbing wildlife or altering natural behavior.

Feeding and baiting: Never feed animals or use bait to attract them for photography. These practices habituate wildlife to humans in harmful ways and can alter behavior patterns. Similarly, never use sound playback to attract birds—it causes stress and energy expenditure during breeding seasons.

Flash usage: Avoid flash in almost all circumstances. Even if technically allowed, flash can startle animals, affect night vision for nocturnal species, and disturbs other visitors’ experiences. Modern cameras handle low light well enough that flash is rarely necessary.

Honest Representation

Disclose significant post-processing in captions if publishing images. Wildlife photography carries an implicit claim of authenticity—viewers assume what they see represents reality. Heavy manipulation, compositing multiple images, or adding/removing elements crosses from photography into digital art, which is fine if acknowledged.

What’s acceptable: Adjusting exposure, contrast, color, sharpness, and cropping are standard practice. Removing small distractions (dust spots, minor branch intrusions at edges) is generally accepted. What’s not acceptable: Adding or removing animals, compositing elements from different images without disclosure, dramatically altering animal appearance or behavior through processing.

Learning from Every Safari

Treat each safari as a learning opportunity. Review your images critically—what worked? What could improve? Study successful wildlife photographers’ work to understand composition, light, and moment capture. Join online communities where you can share images and receive constructive feedback.

Embrace failure: Not every safari produces portfolio pieces. Sometimes light is wrong, animals don’t cooperate, or technical issues intervene. Professional photographers often return multiple times to specific locations for single perfect images. Be patient with yourself and the process.

The real goal: While this guide focuses on technical execution, remember that photography is ultimately about connection—connecting yourself with the natural world and helping others connect through your images. Technical excellence serves that goal but isn’t the goal itself. Sometimes the most meaningful images aren’t technically perfect but capture something authentic and moving about wild lives.

Yala offers extraordinary opportunities for wildlife photography. With proper preparation, technical knowledge, ethical practice, and patience, you’ll return home with images that not only document your safari experience but inspire others to value and protect these magnificent wild places and the creatures that inhabit them.